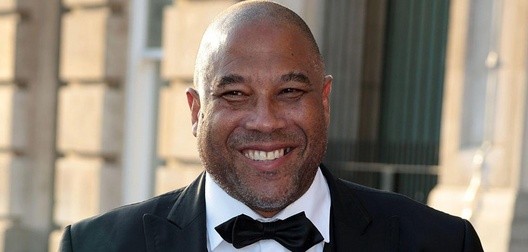

John Barnes: “Football can’t tackle racism until society challenges it”

Alamy

England and Liverpool legend was a groundbreaking figure in the 1980s and 1990s. Now he has written a thoughtful and thought-provoking book that challenges many existing ideas of how racism should be dealt with in football and society.

Barnes argues that football is held up to an unrealistic level of scrutiny and says that society as a whole needs to stop “absolving itself” of its responsibilities towards tackling prejudice by looking at racism as principally “football’s problem”.

Barnes dismisses the idea of affirmative action and says society must change first. “Football can't address those issues. Because how many black people are captains of industry? Any industry? Football isn't different to any other industry.”

22 November 2021 - 6:10 PM

John Barnes bowls past me, a whirl of energy, dodging and weaving a path with the elegance of a master in his trade. At times I feel as if he is running rings around me. At the end of our time I feel chastened and outclassed, like so many men he came up against in his career.

And yet it is 22 years since the former Liverpool and England star last kicked a ball in anger, and today we are not on a football pitch, but sat in our homes face to face over Zoom.

What is going on?

We are talking about race – race and football a bit, but mostly the wider context – and his display is one of verbal brilliance; dazzling, eloquent and one that makes me reconsider many things.

“Football gets a level of scrutiny above and beyond any other industry,” he says.

Alamy: John Barnes, pictured in his playing days with Liverpool.

“Footballers are held responsible for everything. I am a role model for my children. My daughter loves Harry Styles and One Direction, and if she does something wrong because she's copying them, I'll feel that I've let her down myself.

“We're looking for footballers to be the beacons of morality when they're not. They shouldn't be. We all should be. The government should be. We should be as adults, as parents, lawyers, doctors… But unfortunately we just allow footballers to bear the burden of that responsibility.”

Barnes has written a book, The Uncomfortable Truth About Racism. It is a thoughtful and thought-provoking meditation on race, society and history; unusually there was no ghostwriter and he wrote it over a period of “eight or nine years”.

Groundbreaker

His has always been a powerful voice, but his story is all the more remarkable.

The son of a Jamaican diplomat, Barnes relocated to London as a child, joining Watford as a teenager and was part of Graham Taylor’s remarkable early-80s team that finished league and FA Cup runners up.

He joined Liverpool in 1987 and for the next three or four years was one of the best players in the world. He spent a decade at Anfield and in 1999 became the first black manager of a major European club when he was appointed Celtic manager.

Barnes wasn’t the first black England footballer, nor the first to star for a major English club. But he was the first black player in England of world class renown, and was someone who crossed eras from a time where English football stadiums were synonymous with overt racism and violence and into one where the EPL became an international phenomenon.

To a generation of black and Asian kids he was an inspiration. Even to a young fan like me of Liverpool’s bitter rivals, Everton, he was someone who I loved watching.

In short Barnes is someone who should be listened to by football’s leaders, today more than ever before.

For the past two years, the English game has been suffused with race rows forcing out its chairman Greg Clarke last year and seeing the imprisonment of a fan for racially abusing England players after the Euro 2020 final. Shortly before the pandemic it was reported racist incidents were up 50 per cent.

Ten times as much

Barnes, however, has a counter view, and says that British society as a whole needs to stop “absolving itself” of its responsibilities towards tackling prejudice by looking at racism as principally “football’s problem”.

He points to the narrowness and banality of the discourse, by pointing out that racism is now suddenly seen as “cricket’s problem” – after Yorkshire Cricket Club has been consumed by lurid allegations of institutional racism over the past month.

“Football is doing 10 times more than everybody else to tackle racism,” says Barnes.

Chelsea chairman Bruce Buck reveals new thinking on tackling racism in exclusive interview

11 October 2019 - 1:57 PM

Because, he says, the English game is willing to try and take on racism while other industries and sectors of society aren’t “we believe that it's a football problem - and it is not a football problem.”

“Football at least has a sticking plaster [for the problem] and, no one else does. We assume that the problem's in football, but you go around to every other industry and nobody's doing anything. So at least football is doing something: It's highlighting it.”

This, he says, is all football can do. Meaningful change has to come from “society, in communities, people changing the negative perception of what black is.”

“Unfortunately, as long as we just keep expecting football to do more, everyone else just slides by the wayside, under the carpet,” he adds.

Uncomfortable read

His book significantly expands on these themes and is an engaging and at times uncomfortable (as promised by the title) read.

“What we need to do is to explain to people why it’s wrong to be racist, and how we all became racially biased in the first place through unconscious conditioning,” he writes.

“Society needs to learn more about its own history and culture to understand how we got to this position of such unconscious superiority and inferiority.”

Barnes points to the need for broader societal change and education as being the key. But these are changes that will take generations in a society that currently lacks political willingness to take on fundamental questions of racial, social and economic equality.

Alamy: Former Liverpool stars John Barnes, Alan Hansen, Kenny Dalglish and Mark Lawrenson pictured at a funeral.

What can football’s leaders do to extract more immediate change? Barnes quotes Martin Luther King: “The shallow understanding of what is considered to be racial bias by good people is the problem, not the overt racists.”

He says that the game’s leaders need to stop devoting their energy to things that they think are right but don’t ultimately really matter – like condemning Hungarian fans racially abusing England players – and start addressing “the elephant in the room.”

Black man's capability to lead

“Why hasn't anyone mentioned the black of Asian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi footballers?” he asks.

“Why have those very same black footballers, and where are the black managers? Why isn't Sky having a roundtable discussion about the lack of black managers? Is that not racial bias? That is much more of a problem than a Hungarian fan throwing a banana on the field or racially abusing somebody,” he says.

“There are 30 percent black footballers. How many of them are actually retained in the industry after they've retired at any level? But no one's talking about that. Is that not racism? I'd rather see that we are addressing that rather than a Hungarian racist football fan?”

Interview: Football executives needs to wake up to potential of “diversity dividend”

15 December 2020 - 3:19 PM

Can football do anything to tackle this?

“Football can't address those issues. Because how many black people are captains of industry? Any industry? Football isn't different to any other industry. Why do we want football to address it when no one else addresses it?

"And all it boils down to is the perception of a black man's capability to lead. That's what management is.

"Regardless, whether you're a footballer, working at McDonald's, you're working in a bus station. So why is football any different? People are just saying, 'Oh, it's just a problem in football.' But it's a problem in society until we do it the other way round. Tackle it in society - and then all other forms of society, including football, will fall into line.”

Barnes dismisses the idea of affirmative action, including the adoption of the so-called “Rooney Rule” – which demands clubs interview black managers for vacant positions. He says again that most decisions involving race are reactionary.

Does he think that Greg Clarke was right to resign the FA chairmanship last year after referring to black players as “coloured” before parliament?

“Not if Boris Johnson is not going to resign for calling [Muslim women] letterboxes,” he replies, before adding that other industry leaders need to look at how they view equality.

“So no, he was not right to resign.” If Clarke was a precedent: “Everybody else is going to resign.”

Future of activism

Barnes points to the example of Manchester United forward, Marcus Rashford, as representing “the future” of activism.

Rashford, through wealth and fame, says Barnes, has become part of the “black elite”. But all too often those who find themselves in that position focus on what affects them, such as racism in stadiums, which has little or no bearing on most ordinary people’s lives.

“He didn't use his voice to say, 'Oh, stop abusing me',” says Barnes. “He used his voice to say, 'Let us help these underprivileged people'. And he changed government policy by that voice.”

“So yes, we do have to get rid of racism in football, but no one's talking about what's actually going on right here on the streets for our kids and jobs in education, housing, lack of access to social care. And if we are the black leaders - the black elite - let us talk about helping them, not helping more black elite people to become elite.”

The “Black elite” he references should use their positions and platforms to improve the lives of fellow black people.

By improving the lives of black people, he argues, they’ll change the perception of black people, which in turn will see the entire black community prosper.

Privileged background

The power and eloquence of Barnes’s words are striking, and while his views are controversial they are also thought-provoking and at times challenge what I consider myself defining experiences – albeit from a privileged white perspective.

I tell him about watching a Merseyside derby in October 1988, shortly before my tenth birthday, and listening in horror to torrents of racial abuse directed from fellow fans. The match has stayed with me ever since, a source of abiding shame.

Yet Barnes says this never affected him. When I ask why not, he shrugs.

Brentford CEO ready to use Premier League status to help drive public debate in key issues

12 August 2021 - 7:15 PM

“If Robbie Fowler was called a robbing Scouse B, it doesn’t affect him. Robbie Fowler's life has shown him that he's not a robbing Scouse B, hasn't it? My life has shown me that I'm not an N."

He extrapolates on his own childhood, the £3 million house in Highgate where he lived, his father’s chauffeur driven car, life among the diplomatic set.

“So the fact that some ignorant person who is much less well-off than me and can't spell his own name is abusing me. Why is he feeling superior to me and why am I supposed to feel inferior to him?”

Are we in a better place now than we were in 1988?

“Yyou would think we're in a better place because overt racism, overt sexism, overt homophobia is obviously not around anymore in the way that it was,” he says.

“So therefore, we are giving the illusion that we've moved on. But in reality, things aren't getting any better for the inner city whites people who still can't get jobs still can't get housing. And of course, for the inner city black people.

Alamy: John Barnes

“So what we're doing is we're creating more black elites, more female elites. But nothing's changing for the white working classes or the black working classes or the northern working classes.

“So, yes, we can give the illusion that things are getting better, but in reality, things aren't getting better for the majority of people.”